-

Continue reading →: Data, Strategy, Culture & Power (New Book!)

Continue reading →: Data, Strategy, Culture & Power (New Book!)How can we get better data (and better AI) faster? Everyone wants to know. And I’ve spent the past four years using Deming’s System of Profound Knowledge to find an answer… which basically boils down to the fact that the people are the problem, and the people are US. What…

-

Continue reading →: Sausage Program

Continue reading →: Sausage ProgramIn 1984, my dad bought an Apple IIe. He had never used a computer before, and he didn’t actually plan to learn how to use one, but he knew the most successful people were getting computers. As a successful person, he too would get a computer. And like many modern…

-

Continue reading →: Psychological Forces in Data Management

Continue reading →: Psychological Forces in Data ManagementIn Tom Redman‘s excellent 2024 book People and Data, he explains that non-data people are the solution to data problems across an organization! He illustrates how to use Lewin’s Force Field Analysis (FFA; example below) to begin the process of making change actionable. “To accelerate progress, you can enhance the…

-

Continue reading →: How Data Loses Value Over Time

Continue reading →: How Data Loses Value Over TimeMoney loses value over time – and data depreciates too. This erosion of data value occurs through multiple channels, each diminishing the utility and reliability of information as time passes. One of the most insidious ways data loses value is through the loss of context and institutional knowledge. As team…

-

Continue reading →: Process in Service of Value

Continue reading →: Process in Service of ValueThis morning, I was talking to one of my favorite CEOs. He’s thinking through ways to get his teams to focus on real, authentic, meaningful customer value – instead of using process as crutches. You may have experienced something similar. Ever found yourself sitting in yet another sprint planning meeting,…

-

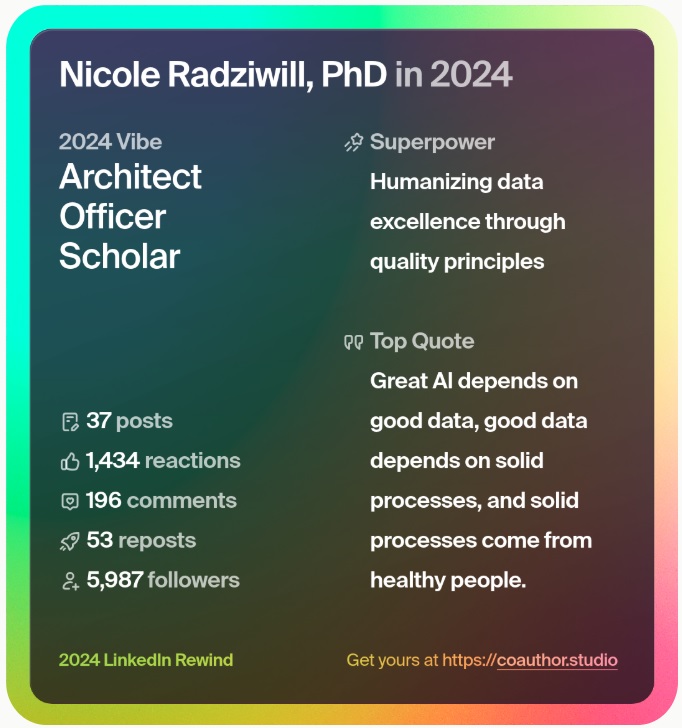

Continue reading →: Looking Ahead to 2025

Continue reading →: Looking Ahead to 2025Here’s my 2024 LinkedIn Rewind, by Coauthor.studio: 2024 proved what quality management pioneers knew decades ago: Great AI depends on good data, good data depends on solid processes, and solid processes depend on PEOPLE collaborating in healthy ways. As organizations rushed to implement AI, the ones that demonstrated early success…

-

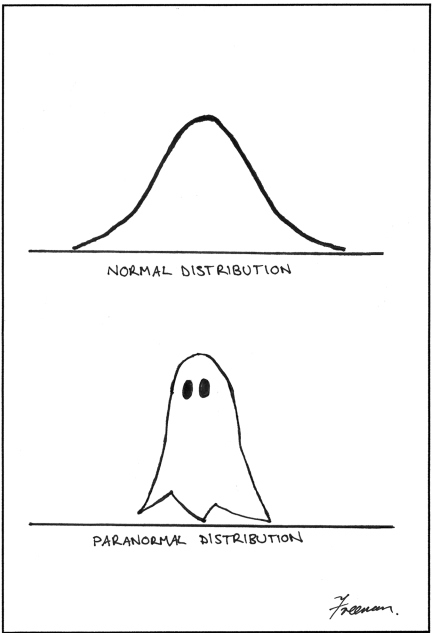

Continue reading →: The Scariest Part of Corporate Halloween

Continue reading →: The Scariest Part of Corporate HalloweenEvery year on this day, statistics and data people are REQIURED to advance data literacy by making sure as many people see this as possible (thanks to Scott for being a first mover on Halloween 2024): But you know what’s REALLY scary? Not understanding distributions! While individual metrics on your…

-

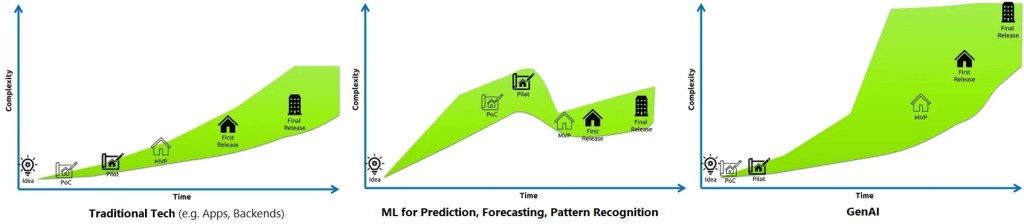

Continue reading →: GenAI: From Proof of Concept to Production

Continue reading →: GenAI: From Proof of Concept to ProductionFor the past year, I’ve been leading AI Product Management for a long-term client. I’ve also been doing a lot of heads-down engineering, building AI agents and API endpoints and orchestrators and automations. I can usually get to IMPRESSIVE PROOF OF CONCEPT (POC) in under a day. Sadly, getting a…

Hello,

I’m Nicole

Since 2008, I’ve been sharing insights and expertise on Digital Transformation & Data Science for Performance Excellence here. As a CxO, I’ve helped orgs build empowered teams, robust programs, and elegant strategies bridging data, analytics, and artificial intelligence (AI)/machine learning (ML)… while building models in R and Python on the side. In 2025, I help leaders drive Quality-Driven Data & AI Strategies and navigate the complex market of data/AI vendors & professional services. Need help sifting through it all? Reach out to inquire – check out my new book that reveal the one thing EVERY organization has been neglecting – Data, Strategy, Culture & Power.